This series highlights the consortium's talented researchers and community partners and their work on health equity. We take a deep dive into who they are, what makes them passionate about their work, and more.

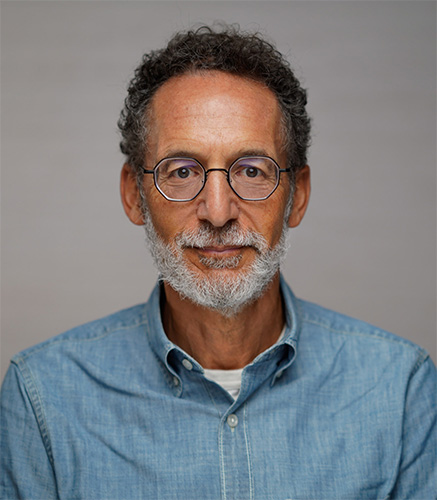

Michael Goran, PhD is Professor of Pediatrics and Vice Chair for Pediatric Research in the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California. He is Principal Investigator and Director at the Southern California Center for Latino Health, and Co-Lead of Project #1.

What kind of research do you do?

Well my own research has been quite sharply focused on looking at the factors contributing to early life risk for chronic diseases, including obesity, Type 2 diabetes and fatty liver disease. And we look at dietary factors, environmental factors, physiological factors and how those contribute to early risk and lifelong risk of these outcomes.

How did you get into health equity research?

Well I’ve always been interested in trying to understand why different groups of populations are at different risks for different things and not even sure when I started looking at that, but it wasn’t called disparities. It was just population differences. And I remember when I was at the University of Vermont thirty years ago, all of our studies – Vermont is about 95% white but I was interested in Native American health because I was doing research in childhood obesity and Native American children have always had much higher levels of obesity and Type 2 diabetes. So I did one small study in a Native American population in Upstate New York and then I moved to Alabama. And in Alabama there was a big interest and big concern in the black population and trying to understand why black kids were getting higher levels of obesity and diabetes at a younger age. So I started to do studies on that in Alabama in the 1990s. And then I moved to Los Angeles in 1999 and where I moved was located at the time at USC. It’s in East L.A., which you probably know if you’re from Los Angeles, to a 95% Hispanic neighborhood. And if you look at the research that was being done at USC or around the country and in publications, very little study among the Latino population, especially not among children. So I just saw it as a huge gap that needed to be addressed. You can see just from the epidemiology that there were much higher levels of these conditions among Latinos but really nobody was studying it and there we were in East L.A. with the population right in the community. So with my background and interests and where I was and what the needs were, that was my first crack when I came to USC in 1999 was to recruit a cohort of Latino children and follow them and try to understand why they were at higher risk for Type 2 diabetes.

Which projects are you part of at Southern California Center for Latino Health?

So at our center we have three projects. I am the co-lead on one of the three projects, which is a – it’s not an intervention study like our other two projects. My project is a longitudinal cohort study so we’ve been following a cohort of a couple of hundred babies that were born, all Latino babies that were born five to seven years ago. We’ve been following them since birth to look at early life nutrition, early life environment, how it’s affecting their growth and development and so the center project is looking at those children age six years of age so all the children in that cohort will come in for testing at age 6. I’m going to make evaluations of their current status of body weight and obesity risk, making measures related to their Type 2 diabetes risk and their fatty liver disease risk, so be able to make pretty careful measurements of where they are on the trajectory and then examine how their early life experiences, whether that's nutrition or environment, how those early life experiences affected their level of risk at age six years of age.

What are the main focuses of your study?

The main focuses are diet, so it’s early life nutrition. That could be looking to see whether they were breast-fed or formula-fed and for how long, even looking at different types of formula and formula and breast milk ingredients, and then with introduction to solid foods we have very detailed measures on nutritional intake in the first few years of life. And in terms of environment, we’re looking at air pollution, in particular, as one of the main outcomes because we’ve shown before that air pollution can be a factor. And then looking at all the social determinates of disease that the center as a whole is also looking at.

What is your favorite part of doing this kind of research?

I enjoy more these days the kind of upper level management aspect. I didn't think I’d ever say that but I’m actually – one of the things the center has provided the opportunity to do is to organize the research and target it towards specific needs and bring people together to get the research that needs to be done, to involve the community. I think the center has afforded a wonderful opportunity with resources to do that, because before, really in my 35 years the only things I was able to do was what I could raise a grant to do and so it’s very limited. It’s kind of one grant, two grants here or there to ask very specific questions, but I think with this center, with the resources that we have, we can ask multiple questions or we can bring people together, we can create a lot of synergy. We can involve the community, we can disseminate; we can fund pilot studies. So I think it’s really – I’m really enjoying that part of really coming up with a strategy to address this issue, not just with my one little grant but with all these different tools in the toolbox to these centers.

Your book, Sugarproof, talks about the dangers of sugar for kids. What are some commonly-consumed food that not many people know about that contains a lot of sugar?

The first half of the book is all about the science of why sugars are harmful to health and why kids are more vulnerable. But the second half is full of those types of practical strategies and tips, call those hidden sugars and that's even the title. “Protect your Family from the Hidden Dangers of Excess Sugars.” So it’s hidden sugars where common foods are high in sugars. Like bread and pasta sauce come to mind, and peanut butters and yogurts which are, you know, lofted and marketed as healthy foods, are often quite high in added sugars. You know, condiments like ketchup, mustard, barbecue sauce, crackers, frozen food, you know, the list goes on. Yeah, so we try to raise awareness not just of the obvious, that there’s a lot of sugar in soda and there’s other things in soda you shouldn't be drinking, but also talk about identifying all these hidden sugars and try to switch to other brands that are healthier and you don’t have the added sugars.

What are some alternatives to soda?

So plain sparkling water is great. Some of the flavored sparkling waters are probably okay, where you can make your own flavored sparkling water, you know, by squeezing juice into plain sparkling water. I think it gets very murky with alternative sweeteners. So a lot of these products have other types of sweeteners in them and this is another area of interest of mine. And we’ve done research on this. There’s other studies showing that the sweeteners are harming the body in ways that we didn't think they would. So diet soda is not the solution because the chemicals in diet soda are causing problems, different problems, and aren’t resolving our craving for sweetness. So basically, you know, as a society we have a very sweet tooth, right? We like sweet treats and, you know, I do too. I’m not saying I don’t but these alternative sweeteners aren’t helping with that and also they’re creating this false sense of sweetness because they’re not real sweeteners and they kind of trick the system as well. So we have to be a little bit careful there. I think the diet soda business is huge right now and that's how the industry responded, the industry saying, “Oh, we need to have people consume less soda. We’re just going to make more diet soda.” But your initial reaction was spot on. I think flavored waters are a much better place to go, especially if they’re naturally flavored.

What do you do outside of work?

My family’s always teasing me because I’m always experimenting with drinks. The other day – because I also like tea and these days I’m making a lot of iced tea – so sometimes I’ll mix Topo Chico in with my iced tea so it’s a little bit bubbly. And then the other day I was feeling a little dehydrated so I put some coconut water into my iced tea. So I’m always like experimenting with different blends.

Outside of mixing drinks, do you have any other hobbies you enjoy?

I’m an avid tennis player so I like to play tennis. That's my main form of exercise and destressing. I wish I could play every day. I go and I maybe play a couple times a week,

What advice would you give to others in your field?

Yeah, it’s a tough career but it’s fun and it’s rewarding. It’s not immediate gratification so you have to kind of be patient. I think persistence and resilience are both important. A lot of the good stuff we’ve done didn't come easy. It often can take years to get a project funded, years to get the project done, so you have to be very patient, passionate and resilient. That's kind of three words that come to mind. I do a lot of mentoring and talking, helping mentor younger investigators. Collaboration is important and that's another reason why I like this center because it’s very collaborative. It’s not for everyone but many of the younger investigators, you know, are very keen to collaborate. That's great. So, you know, those are the kind of simple things that come to mind. It’s challenging but, you know, you’ve got to stick with your ideas, believe in your own ideas and don’t give them up just because some random study section didn't like your grant idea. You’ve got to keep working on it and make it better.